Animal Talk Animal Communication Penelope Smith

- ©2026 Penelope Smith 0

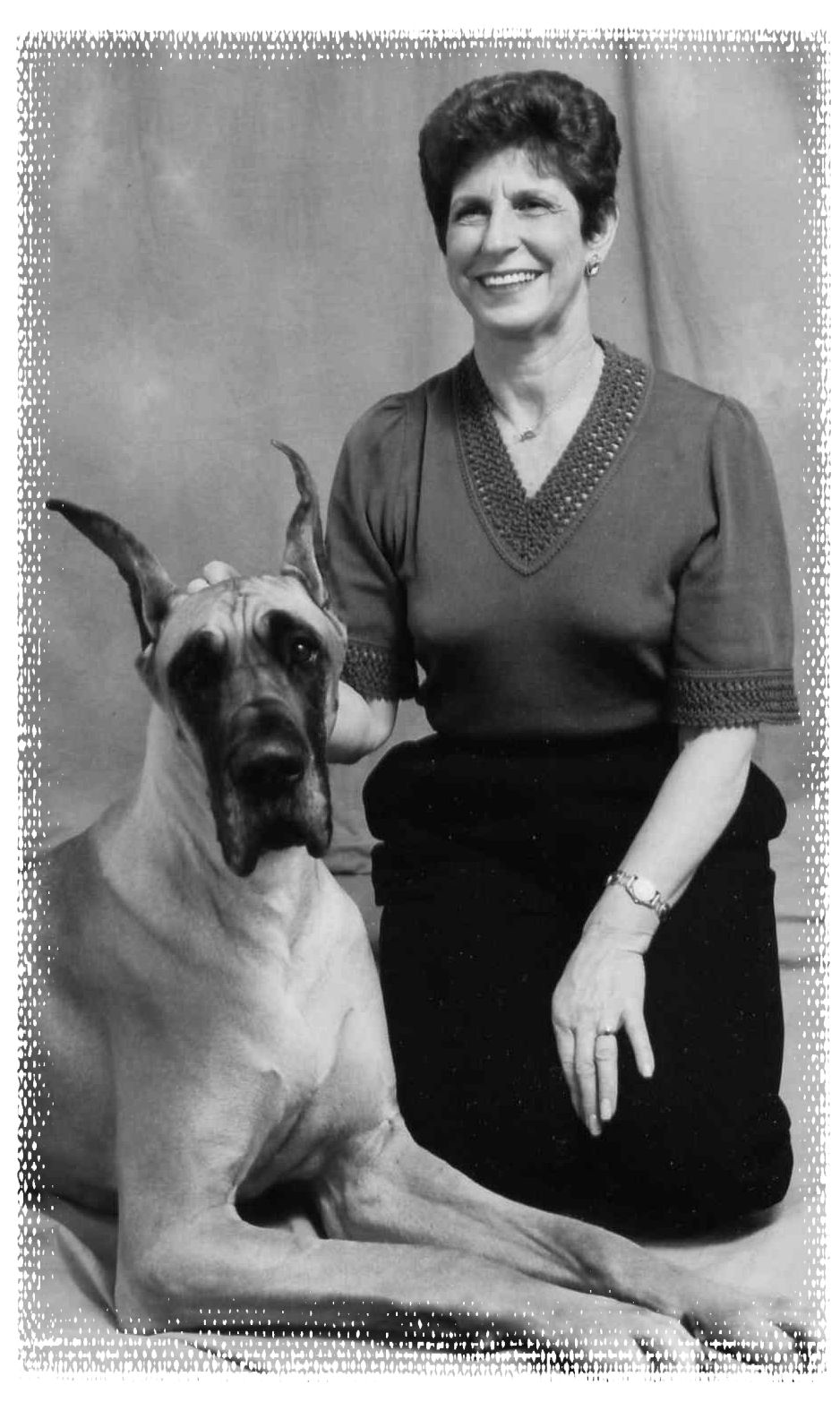

Betty Lewis has been an animal communicator since 1981. A well-seasoned, down-to-earth practitioner in the field, she brings an exceptionally high level of training and broad background in holistic methods to her work. Betty’s training and experience illustrate what it means to be a well-rounded and grounded animal communicator.

Betty Lewis has been an animal communicator since 1981. A well-seasoned, down-to-earth practitioner in the field, she brings an exceptionally high level of training and broad background in holistic methods to her work. Betty’s training and experience illustrate what it means to be a well-rounded and grounded animal communicator.